Tired, Foggy, and Unfocused?

It Might Not Be ADHD, It Might Be Anemia.

Why Every ADHD Assessment Should Include an Anemia Screening

If you’ve ever felt like your ADHD symptoms flare with fatigue, brain fog, irritability, or even depression, you’re not imagining it. Research increasingly shows that low iron levels and anemia can both mimic and amplify ADHD symptoms, affecting focus, energy, and emotional balance.

In fact, several studies show that up to 84% of children with ADHD have low iron status or anemia, and that having low ferritin or hemoglobin can increase ADHD symptom severity by up to 50%. That’s a huge overlap — and one that often goes unaddressed in traditional care.

So before adding another supplement or increasing stimulant medication, it’s worth asking:

Could low iron (or a nutrient deficiency causing anemia) be part of what’s driving your symptoms?

Let’s look at the science behind this powerful connection, what labs actually matter, and how a functional approach can bring clarity and calm back to your mind and body.

Anemia and ADHD:

Two Conditions with Shared Symptoms

Both anemia and ADHD can present with:

Brain fog

Irritability or mood swings

Fatigue or low motivation

Headaches

Restlessness

Low stress tolerance

Poor focus or attention

Depression or anxiety

It’s easy to see how one can mask the other.

If you’re low in ferritin (your stored iron) or other nutrients that support oxygen delivery and neurotransmitter balance, your brain is literally running on low fuel.

This can make ADHD symptoms look worse, even if your underlying neurotype isn’t changing.

The Role of Iron:

Fuel for Focus and Neurotransmitters

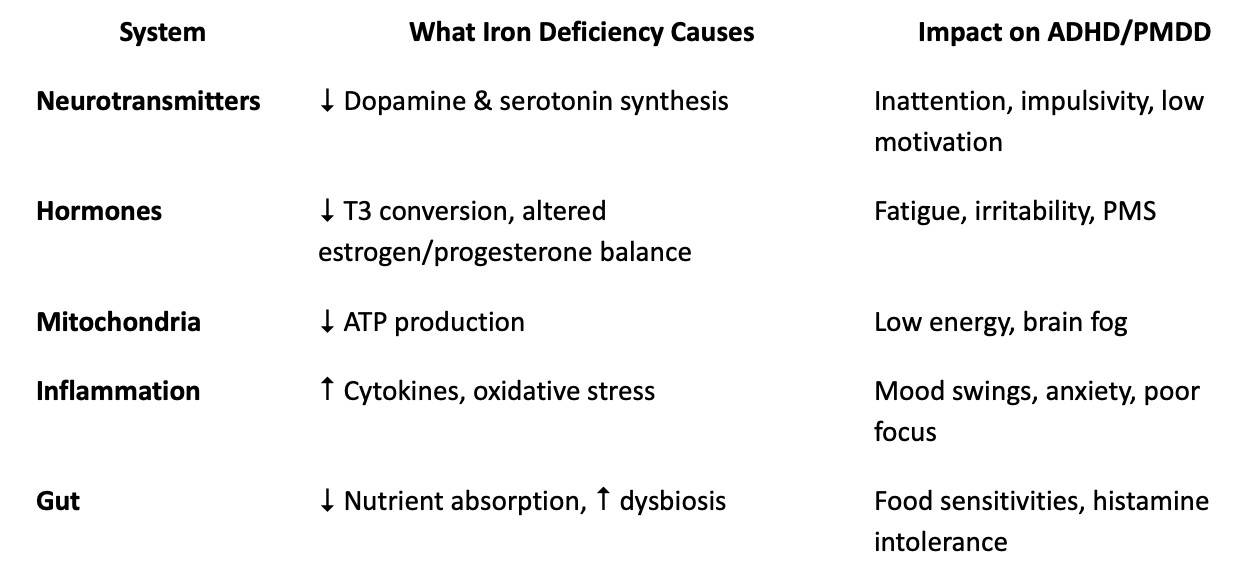

Iron isn’t just about red blood cells, it’s an essential cofactor in dopamine synthesis.

Dopamine is one of the key neurotransmitters involved in motivation, attention, and emotional regulation, the same pathways that are dysregulated in ADHD and PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder).

To make dopamine, your body uses an enzyme called tyrosine hydroxylase, which requires iron to function properly. When ferritin drops too low, your brain can’t make enough dopamine — leading to symptoms that mirror inattentive or combined-type ADHD: trouble focusing, low motivation, mood changes, even impulsive or restless behavior.

Research confirms this link:

Low ferritin is consistently associated with more severe ADHD symptoms (Nowak et al., 2021).

Iron deficiency reduces dopamine receptor density and disrupts signaling in the striatum and prefrontal cortex — key brain regions for focus and executive function (Lozoff 2020; Gustavsson 2023).

Iron and dopamine metabolism are tightly interlinked; when either is out of balance, the other suffers (Hare & Double 2016).

This means that low iron doesn’t just make you tired, it can actually change how your brain processes information and regulates emotions.

Low Ferritin = Low Focus

Ferritin measures your stored iron, and functional medicine often considers anything under 50 ng/mL as potentially sub-optimal for brain and energy function — even if it’s still within a conventional “normal” range.

When ferritin dips too low:

Dopamine synthesis slows.

Energy production in the brain declines.

Mood and motivation drop.

Cognitive performance and focus suffer.

It’s not just fatigue — it’s biochemistry.

Inflammation, Gut Health, and Iron Absorption

One reason so many people remain iron-deficient even with supplementation is gut health. Iron needs a healthy digestive system, and adequate stomach acid for absorption.

Here’s what happens when the gut is off balance:

Low hydrochloric acid (HCl) or digestive enzymes impair iron release from food.

Chronic inflammation, parasites, or dysbiosis (like Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, or Citrobacter on a GI-MAP) damage the intestinal lining, making absorption harder.

Infections and high histamine activity trigger the body to lock iron away as a protective response — a process called “nutritional immunity.”

That means if your gut is inflamed, you could be eating plenty of iron but still not absorbing it. This is where functional lab testing shines: it helps identify whether anemia is caused by poor intake, poor absorption, or chronic inflammation.

The Iron–Thyroid Connection

Iron also plays a key role in thyroid hormone conversion. It’s a cofactor for thyroid peroxidase (TPO), the enzyme that converts T4 into the active hormone T3. Without enough iron, T3 production slows, and symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, cold hands, and low mood appear, all of which overlap with ADHD and depression. So, if you’ve been told your thyroid labs are “normal” but you still feel sluggish, low ferritin may be the missing piece.

The Dopamine–Iron Relationship:

A Two-Way Street

Studies using brain imaging (Gustavsson 2023) show that iron and dopamine are co-localized in the prefrontal cortex and striatum — two regions that regulate attention and emotional control. When iron stores are low, dopamine receptor activity drops. When unbound iron is high, oxidative stress damages these same neurons.

Hare & Double (2016) call this the “toxic couple” — both essential and potentially harmful when unbalanced. Low ferritin means dopamine production stalls; too much unbound iron promotes oxidative stress that breaks dopamine down faster.

In short:

Low iron = not enough dopamine.

High unbound iron = dopamine damage.

Both can mimic ADHD, anxiety, or mood swings.

Histamine, Hormones, and PMDD

Iron and dopamine aren’t the only systems affected. In women with PMDD or perimenopausal symptoms, iron status also influences estrogen, progesterone, and histamine metabolism.

Low ferritin can worsen PMS or PMDD through:

Reduced progesterone sensitivity (progesterone calms the nervous system).

Heightened histamine reactivity — more irritability, headaches, and bloating.

Increased inflammatory cytokines that amplify mood swings.

When combined with luteal-phase hormone drops, these biochemical shifts can create the emotional rollercoaster so many women describe before their period. Functional lab testing helps connect these dots: a DUTCH test can show progesterone levels and cortisol rhythm, while a GI-MAP or OAT test can reveal histamine-producing bacteria or impaired detox pathways.

What the Research Shows

Let’s look at what the science says across multiple studies:

Nowak 2021: Children with ADHD had significantly lower ferritin and hemoglobin levels than controls. Supplementation improved focus and reduced hyperactivity scores.

Pivina 2019: Iron deficiency reduces dopamine transmission and worsens ADHD symptoms; restoring iron improved behavioral and cognitive outcomes.

Lozoff 2020: Low brain iron during development alters dopamine receptor density and myelination, leading to lasting cognitive changes.

Meyer 2024: Dysregulated brain iron contributes to neuroinflammation and oxidative stress — both common in ADHD and depression.

Engle-Stone 2017 (BRINDA Project): Up to 60% of anemia cases worldwide are linked to iron deficiency; ferritin should always be interpreted alongside CRP to account for hidden inflammation.

Together, these studies confirm what we see clinically: anemia and iron imbalance can drive ADHD, PMDD, and depression symptoms through inflammation, neurotransmitter disruption, and poor nutrient utilization.

Functional Lab Testing for Anemia and ADHD

Conventional screening often stops at a basic CBC and iron panel, but functional testing digs deeper. Here’s what I typically assess for clients with ADHD, fatigue, mood swings, or suspected anemia:

1. CBC (Complete Blood Count) Looks at hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and red cell distribution width (RDW). Elevated RDW or low MCV may indicate iron, folate, or B12 deficiency — even before anemia is advanced.

2. Ferritin Reflects your stored iron. Optimal brain and energy function often require levels between 50–90 ng/mL (not just the conventional “normal” range of 15–150).

3. Iron, TIBC, and % Saturation These values help determine whether iron is low because of poor intake, poor absorption, or inflammation.

4. Folate and Vitamin B12 Both are essential for red blood cell production and dopamine metabolism.

5. Vitamin C Supports iron absorption and reduces oxidative stress; low levels can worsen anemia and inflammation.

6. CRP (C-Reactive Protein) or hs-CRP Indicates systemic inflammation that can hide true iron deficiency.

7. OAT (Organic Acids Profile) Shows downstream markers of dopamine (HVA, DOPAC), energy metabolism, and oxidative stress.

8. GI-MAP (Stool Test) Identifies inflammation, malabsorption, and gut pathogens that interfere with nutrient uptake.

9. DUTCH Test (Hormones) Reveals how estrogen, progesterone, and cortisol interplay with mood, stress, and histamine.

10. HTMA (Hair Tissue Mineral Analysis) Evaluates mineral patterns (iron, zinc, copper, magnesium) that affect detoxification, neurotransmission, and stress resilience.

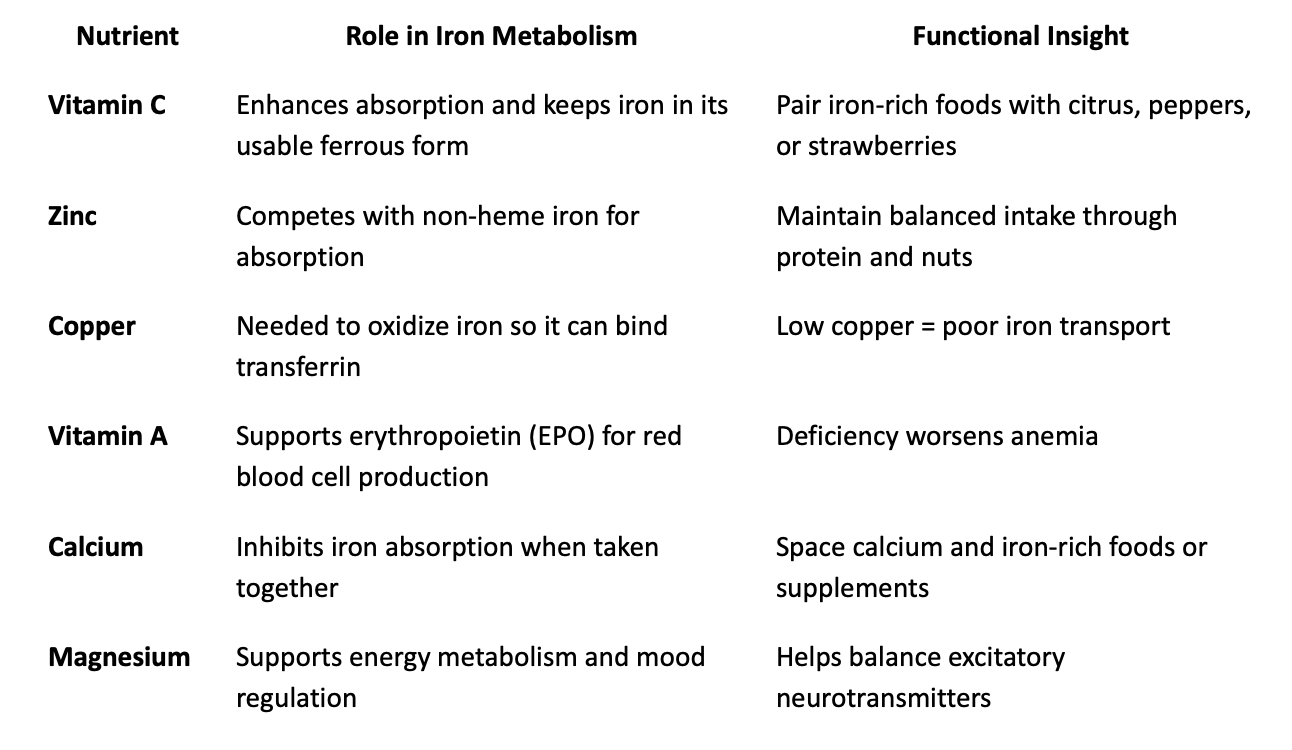

How Iron Interacts with Other Nutrients

Iron rarely exists in isolation. It depends on a network of nutrients to function properly:

How Anemia Worsens ADHD, PMDD, and Depression

Let’s connect the dots:

Practical Tips for Supporting Healthy Iron and Focus

While your individualized plan should always be based on lab data, here are some general functional strategies I use with clients:

1. Support Absorption

Eat iron-rich foods (grass-fed beef, chicken liver, lentils, spinach, pumpkin seeds).

Pair with vitamin C-rich foods like citrus, bell peppers, or berries.

Avoid coffee or tea with meals — they can reduce iron absorption by up to 40%.

Cook with a cast-iron skillet to boost non-heme iron intake naturally.

2. Calm Inflammation

Use omega-3s, curcumin, and a low-histamine, anti-inflammatory diet.

Identify gut pathogens or sensitivities with stool testing.

3. Restore Gut Integrity

Include carminative and digestive herbs like ginger, fennel, chamomile, or bitters before meals.

Support stomach acid and enzymes if low (especially after long-term PPI use).

4. Rebalance Nutrients

Ensure adequate copper, zinc, B-vitamins, and magnesium to help your body use iron properly.

5. Regulate Hormones

Track cycles if you have PMDD or heavy bleeding — iron loss each month adds up.

Support progesterone naturally with nutrients like vitamin B6, magnesium glycinate, and stress-reducing practices.

Functional Testing in Action: My Approach

In my clinic, I often see patients who were told their “labs look normal” yet still struggle with fatigue, ADHD symptoms, and mood swings. Once we run functional panels like the OAT, GI-MAP, or HTMA, the picture becomes clear.

Many show:

Sub-optimal ferritin

Gut inflammation limiting iron absorption

Oxidative stress on the OAT

Neurotransmitter imbalances affecting dopamine and serotonin

By addressing these root causes, focus improves, energy stabilizes, and emotional resilience grows. It’s not about quick fixes, it’s about uncovering the “why” behind your symptoms.

How I Can Help

I offer personalized 1:1 functional medicine consultations and lab-based programs designed to uncover the biochemical root causes of ADHD, PMDD, and fatigue.

Together, we’ll create a plan that supports nutrient balance, neurotransmitter health, and hormonal harmony.

If you’ve been struggling with:

Fatigue that feels deeper than tiredness

ADHD or focus issues that worsen around your cycle

Normal labs that don’t explain how you feel

— then it’s time for a deeper look.

Book a discovery call to explore whether a functional lab analysis could help you connect the dots.

It’s Time to Stop Guessing

Anemia and ADHD share more than symptoms, they share biochemistry. If you’re low in ferritin, struggling with focus, or noticing emotional ups and downs, don’t settle for “your labs look fine.” With the right testing and a root-cause approach, you can finally move from guessing to knowing and from surviving to thriving.

References

Engle-Stone, R., Aaron, G. J., Huang, J., Wirth, J. P., Namaste, S. M., Williams, A. M., Peerson, J. M., Rohner, F., Varadhan, R., Addo, O. Y., Temple, V., Rayco-Solon, P., Macdonald, B., & Suchdev, P. S. (2017). Predictors of anemia in preschool children: Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 106(Suppl 1), 402S–415S. https://doi-org.proxy-ln.researchport.umd.edu/10.3945/ajcn.116.142323

Gustavsson, J., Johansson, J., Falahati, F., Andersson, M., Papenberg, G., Avelar-Pereira, B., Bäckman, L., Kalpouzos, G., & Salami, A. (2023). The iron-dopamine D1 coupling modulates neural signatures of working memory across adult lifespan. NeuroImage, 279, 120323. https://doi-org.proxy-ln.researchport.umd.edu/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.120323

Hare, D. J., & Double, K. L. (2016). Iron and dopamine: a toxic couple. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 139(Pt 4), 1026–1035. https://doi-org.proxy-ln.researchport.umd.edu/10.1093/brain/aww022

MacLean, B., Buissink, P., Louw, V., Chen, W., & Richards, T. (2025). Women with Symptoms Suggestive of ADHD Are More Likely to Report Symptoms of Iron Deficiency and Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. Nutrients, 17(5), 785. https://doi-org.proxy-ln.researchport.umd.edu/10.3390/nu17050785

McWilliams, S., Singh, I., Leung, W., Stockler, S., & Ipsiroglu, O. S. (2022). Iron deficiency and common neurodevelopmental disorders—A scoping review. PLOS ONE, 17(9), e0273819. https://doi-org.proxy-ln.researchport.umd.edu/10.1371/journal.pone.0273819

Morandini, H. A. E., Watson, P. A., Barbaro, P., & Rao, P. (2024). Brain iron concentration in childhood ADHD: A systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 173, 200–209. https://doi-org.proxy-ln.researchport.umd.edu/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.03.035

Nowak, S., Wang, H., Schmidt, B., & Jarvinen, K. M. (2021). Vitamin D and iron status in children with food allergy. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, 127(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2021.02.027

Pivina, L., Semenova, Y., Doşa, M. D., Dauletyarova, M., & Bjørklund, G. (2019). Iron deficiency, cognitive functions, and neurobehavioral disorders in children. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 68(1), 1–10. https://doi-org.proxy-ln.researchport.umd.edu/10.1007/s12031-019-01276-1

Robberecht, H., Verlaet, A. A. J., Breynaert, A., De Bruyne, T., & Hermans, N. (2020). Magnesium, iron, zinc, copper and selenium status in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(19), 4440. https://doi-org.proxy-ln.researchport.umd.edu/10.3390/molecules25194440

Wiegersma, A. M., Dalman, C., Lee, B. K., Karlsson, H., & Gardner, R. M. (2019). Association of prenatal maternal anemia with neurodevelopmental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(12), 1294–1309. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2309